This is the fourth part of the series. The author focuses here on Islam’s golden age and its effect on the Jewish-Muslim relations. He also highlights the relation between political Islam and anti-Semitism. Click to read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

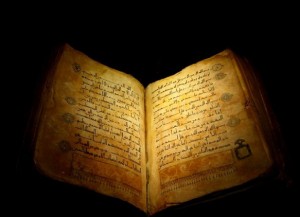

Islam’s Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age, from 750 c.e. to 1257 c.e., was a period of unparalleled intellectual accomplishment in mathematics, astronomy, chemistry, medicine, architecture, literature, and philosophy. It was also a period marked by political and economic success, and ecumenical tolerance. Although there were exceptions, Muslims, Jews, and Christians prospered and coexisted throughout the Islamic world in relative peace within the framework of the policy of the Rules of the Protected Minorities.

The success of the policy was evident particularly in medieval Muslim Spain, where Muslims and Jews together built a civilization, known as Al-Andalus, which was more advanced than any in Europe at that time. However, when Muslim Spain fell to the Christian armies in 1492, most of Spain’s Jews were expelled. Many immigrated to Palestine, where they were given asylum by Palestinian Muslims. The inquisition eliminated those Jews who remained. Even during the most oppressive periods in Islamic history, Jews under Muslim rule received far better treatment and had greater rights than they did under Christian rule in medieval Europe.

Baghdad was the raison d’être and crowning achievement of the Golden Age of Islam. During the Abbasid caliphate from the 9th through the 13th centuries, Baghdad was the principal trading hub in the Islamic Empire. The city also was where Muslim, Jewish and Christian scholars from throughout the world came into contact with one another, and shared their knowledge, literature, language, and faiths.(1) The educational roots of Muslim scholars and jurists were in Baghdad during this period, as well.(2) The cosmopolitan city became the cultural and intellectual center of the world,(3) as well as the primary location for translation into Arabic of classical Greek texts and other important scholarly writings. With the development of cotton and hemp paper, books copied and produced in Baghdad filled libraries throughout the Islamic world, thereby facilitating the transition from oral to written communication in West Asia and the Middle East.

The ‘Long Twilight of the Late Islamic Middle Ages’

In the 13th century, regional economies began to stagnate, and the Muslim Middle East entered a prolonged period of decline which historians refer to as “the long twilight of the late Islamic Middle Ages.” While there were multiple causes for the decline, there is general agreement among historians that the end of Islam’s Golden Age was precipitated by the devastating invasions into West Asia and the Middle East by Genghis Khan and his Mongol Turkic tribes, and the Crusaders’ incursions into the Holy Land. The Mongols’ invasion left in its wake a swathe of ruined cities, libraries, and mosques. They destroyed northern Iran and decimated the ancient irrigation systems of Mesopotamia. With regional and local economies imperiled, people of all religions and ethnicities suffered immeasurably.

The Islamic Golden Age and Baghdad’s reign came to a tragic and abrupt end in 1258 c.e. with the Siege of Baghdad by Mongol forces led by Hulagu Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan. Conservative estimates indicate that more than 100,000 people were massacred, and that the city’s libraries and schools were completely destroyed. It was said that Baghdad’s streets “ran red with the blood of scholars”, and the Tigris River “ran black with the ink of books.

In reaction to the irreplaceable loss of learning of the past resulting from the destruction of manuscripts and the slaughter of scholars, Muslim societies turned inwards and became more conservative. The struggle to preserve Islamic religious traditions and recover what had been lost impacted Islamic jurisprudence. Up to this point, the work of Shari`ah jurists had been characterized by independent legal reasoning, or ijtihad. The jurists now turned to the practice of taqlid, or imitation, arguing that there was no need to formulate new rules as all the rules of law had been expounded. The net effect was a virtual ossification of Islamic law and learning.(4)

Political Islam and Anti-Semitism

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, the Middle East and Asia gradually came to be dominated by British and European colonial powers pursuing natural resources to fuel the engines of their new economies. As agrarian economies in Asia and the Middle East contracted, the specter of religious intolerance and persecution of dhimmis in Muslim societies grew. Lacking understanding of the nature and impact of industrialization that was occurring throughout the world, and ill-prepared to adapt, Muslim societies blamed others – foreigners, outsiders, dhimmis — for their languishing economies and waning independence. Ethnic and religious rivalry and victimization increased, and the status of Jews in the Muslim world deteriorated accordingly.

As has been shown, anti-Semitism is not supported in the Qur’an, and contradicts the life and teachings of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). Nevertheless, the amalgam of the Mongol invasion, the Crusades, the industrial revolution, and the rise of British and western European colonialism generated the ideal conditions — a perfect storm — for virulent anti-Semitism to gain a foothold in the Muslim world.

It was left to Nazi Germany to propel anti-Semitic narratives in the Middle East. In the 1930s, pursuing hegemony in the region, Hitler’s agents incited anti-Jewish hatred amongst Muslims in Egypt and Palestine with propaganda, weapons, and money. As WW II drew to a close, the core of anti-Semitism began to shift from Germany to the Arab world. With the Balfour Declaration and the creation of the state of Israel, anti-Semitism took root in various Muslim nationalist political movements, particularly in the Middle East.

The specter of anti-Semitism plagues Islam to this day, essentially for the reasons that it appeared during the decline of Islam’s Golden Age and later in the colonial period. Invariably, racial, ethnic and religious minorities are blamed, marginalized and attacked whenever and wherever there are conditions of political oppression, foreign supremacy, extreme poverty, and unequal distribution of scarce resources.(5) Diverting attention from the actual, often intractable causes of social, political, and economic problems by projecting or transferring blame onto “others” — those who are different by virtue of race, ethnicity, nationality, religious and/or political beliefs, is a demagogic propaganda strategy as old as civilization itself.

References:

(1) Cooperson, Michael, “Baghdad in Rhetoric and Narrative”, Muqarnas (1996) 13:100.

(2) Robinson, Chase, Islamic Historiography, (2003) New York: Cambridge UP, p. 27.

(3) Gaston Wiet, Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate, Univ of Oklahoma Press, Ch. 5.

(4) Kareem Elbayar, Reclaiming Tradition: Islamic Law in a Modern World, International Affairs Review, Vol. XVII, No. 1: Spring/Summer 2008.

(5) See: Islam and Politics, by John Esposito, 4th ed., 1998.

To be continued…

____________________

This series of articles is published with kind permission from the author.

Arabic

Arabic English

English